As those of you who pay any attention to me on Facebook will be aware, I’ve finished Graham and Trevor, and they do look handsome:

There are a lot of things that could do with more work – the NMM is a bit lacklustre in the hand (although I’m very happy with the axe head), the algae on the boat isn’t terribly prominent or obvious, lots of bits are rough, etc.

However, this was really a practice piece to get me into flats – figuring out how the light works, and all that – and I’m really happy with the result for a first effort. I’m especially pleased with how the water came out – that’s not part of the piece, but I thought it would help sell the scene.

So, rather than dealing with sculpting, I thought I’d do another flat, hopefully putting all the things I’ve learnt into practice. After a few sessions, I have this:

So far, the face, stockings, gloves and his left leg are done, although I’ll probably keep poking at them as the piece progresses and I get a better idea about how the colours balance and how the light should fall across the piece.

Anyway, I began this piece assuming he (Dave) was Spanish, based almost solely on the wee goatee and some vague memories of conquistadors dressing like this. However, when I went to look for some reference images to pick colours, it turned out I was dead wrong.

This is where research comes in. In historical painting, research is very important, especially for competitions.* If you don’t know the right colours and materials, you’re liable to do something based on what you think it should be, and it’s reasonable to assume that a judge knows, for a definite fact, what it should be, and that’s where you lose points.

Beyond just pleasing the judges, part of the reason a lot of people paint historical pieces is out of some respect for the past, and often for the characters they’re painting (I’d like to think there’s less of that when painting Nazis and Confederates, but the jury is still out on that one…). As such, it’s really more respectful to try to faithfully recreate the uniform and setting.

* A caveat: I do think the ‘rule of cool’ should pretty much always win – after all, a lot of the pieces that end up being made into models are based on artwork, and the artists who painted these things are as prone to interpretation and adaptation as the rest of us. Not to mention that, when a piece is based on a famous figure from history, the art is usually commissioned by that person, and the artist really wants to get paid and not beheaded, so there’s often a degree of polishing to make sure the portrait or sculpture is suitably flattering.

So, when I realised that this bloke was indeed not a Spaniard, I had to figure out what he could be, and that’s where the internet really comes in handy. I don’t have a complete library of Osprey references to rummage through, but the internet does.

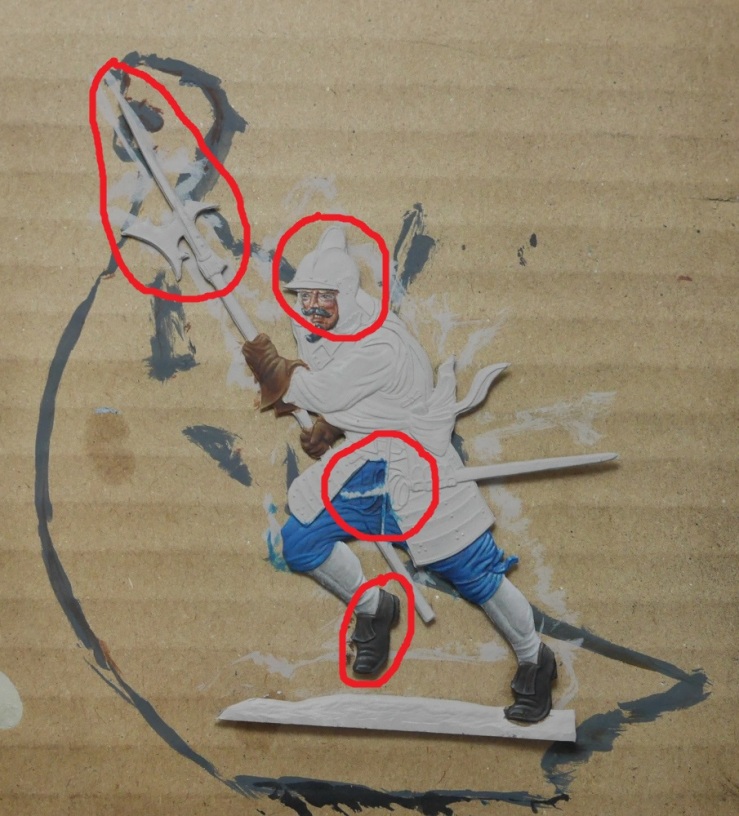

The first thing, of course, was to try to narrow my searches down from just ‘halberdier’. Halberds, as you might have some inkling, were popular weapons for an astonishingly long time. For that, you need to pay some attention to the piece you’re painting and focus on key details that might be regionally or historically distinct. I’ve marked the key things I was looking at in glorious technicolour below:

These are the sorts of things that, from my experience, are pretty clear markers of times and/or locations.

The halberd head is a good one to start with, because you can look at the design, do a quick Google image search for ‘halberd heads’ and find something that’s either exactly right or pretty similar. What I came across was an ornate one from the guard of Emperor Matthias of the Holy Roman Empire. He was around in the early 17th century, which seemed about right for the rest of the figure, so I set about trying to find some references for it. Sadly, the helmets didn’t match.

In the 17th century, a lot of soldiers were still fairly irregular, so uniforms were whatever they had to hand or whatever their boss was willing to buy for them, so I might’ve gotten away with it, except that Matthias’s guard was obviously a professional unit and wore matching uniforms, as befits someone whose death was about to kick off the Thirty Years’ War (which started with the infamous Defenestration of Prague).

So, I moved on to identifying the helmet, which turned out to be a burgonet. These were popular around the same time, so I was able to reasonably assume that this guy was a soldier in the Thirty Years’ War.

As I looked through images of soldiers from that war, however, I came across a few pictures that were pretty much right – notably down to the sword and shoes, and some displaying a sash, too. It turns out they weren’t pictures of the Thirty Years’ War at all, but Dutch soldiers from the Eighty Years’ War, which was the Dutch war for independence from Spain and happened at about the same time.

So, in the end, not only was this guy not Spanish at all (although I suppose the Spanish at the time probably considered them Spanish – or at least part of Spain), he was, in fact, fighting against Spain. I was simultaneously completely wrong and so very, very close.

Based on that, I saw an outfit I liked the look of and decided to dress Dave in that. I’m sure he’ll look suitably handsome and rebellious.

Caveat: I could be completely wrong, but I spent literally hours doing this research and Dave was naked. If anyone knows better, please let me know. I might still have time to correct things.